The COVID-19 pandemic has badly affected the real estate sector in India, which was already struggling with a number of issues including sluggish sales. To get an understanding of what this means for the housing market, the IHR team spoke to Pankaj Kapoor (PK), Managing Director, Liases Foras, which conducts data-driven market research on the real estate sector in India. We asked him about the effects of the pandemic and future prospects for the sector, which is an important supplier of housing in India. Edited excerpts:

IHR: How would you describe the state of the real estate market, with a focus on housing? What were things like before COVID-19 impacted India?

PK: Pre-COVID, inventories were growing faster than sales while prices had not been growing since 2014. The builders’ cost of construction and finance costs were increasing but the credit flow in the market was reducing. They were not finding enough avenues to raise further capital, especially for the housing sector. Despite the growth, there was stress in the market. The growth in sales was 20-25% at an all-India level but the growth in inventory from 2014 till now was around 2.5 times. The builders’ commitment to produce had increased but the sales hadn’t increased in tandem, making it unsustainable. They were already on a slippery curve before the pandemic.

Across India, we had around 13,50,000 unsold units while annual sales were 3,50,000 units. This means that around 4 years of supply was available in the market. Builders had made several commitments with the land purchases due to ample financialisation that happened since 2005, resulting in a big pipeline of new supply. With prices stagnant, builders had to improve their cash flow by launching new projects and rationalizing their supply and prices. This was the basic reason that inventory was continuously growing. The market was in a very uncontrolled state, builders were over-committed, over-leveraged and unsustainable.

CPR: The lockdown itself brought everything to a standstill in terms of activities, so what happened with real estate at that point in time?

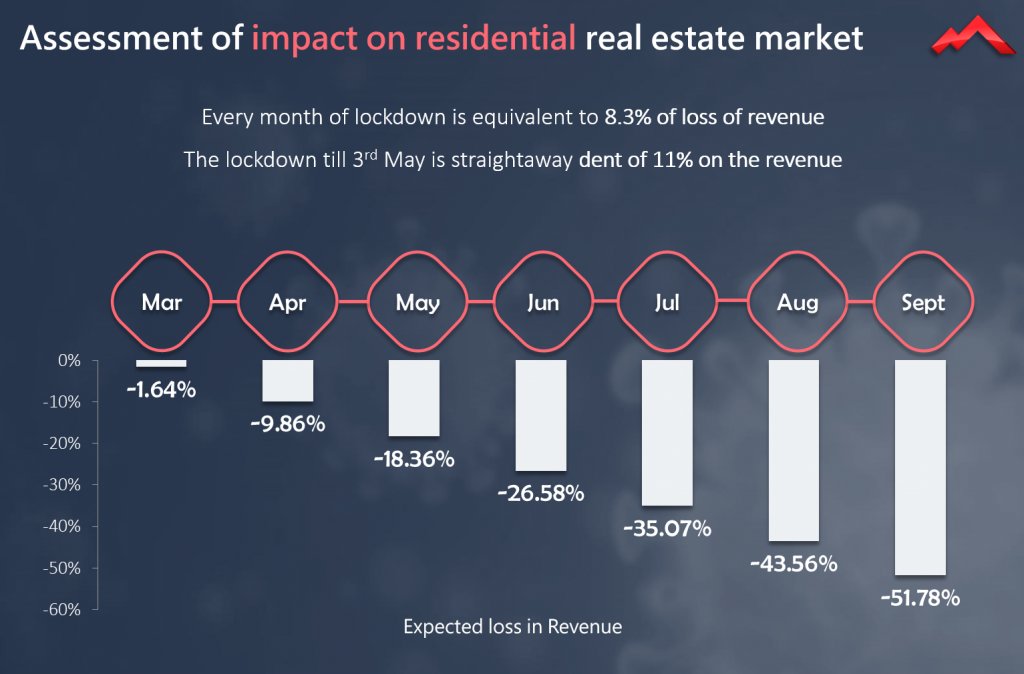

PK: The lockdown has eroded the opportunity to sell and growth and the demand will be impacted quite a lot. Think about it, every month of no activities and sales is impacting the residential real estate market revenues by 8.3%. Although now, after almost 3 months, there’s a partial opening, it is insignificant as the real estate activities haven’t really started. Workers have gone away, and consumers are highly skeptical about buying, partly due to the increased execution risk in under-construction properties. The situation has worsened with the ongoing lockdown and we fear that it may continue for longer because the numbers (of COVID cases) are increasing.

Along with all this, we are seeing corporates rationalizing their costs through salary cuts and layoffs due to declining revenues. It’s a very uncertain market and consumers will think twice before purchasing property. Builders haven’t blinked with motivating offers and the government hasn’t implemented demand-side interventions. The 20 lakh crore rupees worth of stimulus announced by the central government is just supply-side intervention and the demand-side is still at a standstill, becoming worse day by day.

IHR: You had mentioned a very interesting series of possible lockdown timelines and the impact of each of those scenarios on the real estate sector. What did you imagine when you were building those scenarios and actually played out on the ground?

PK: We built the scenarios considering that we were still in the spreading mode of the virus. We also took a queue from some of the emerging markets and their timelines, speaking to some IT companies connected to European and US markets. They estimated the impact to last till September, which is why kept at least a 6-month period impact in our analysis.

Bringing back the workers is another big cost which we have taken into account. Currently, the economic loss has caused the government to force open the economy, but not in places like Mumbai which contributes around 20% of the overall real estate in India in terms of value. Chennai and some other geographies have started moving a little better than other cities, but real estate activities are still at 15-20% of their pre-COVID levels.

IHR: The Real Estate Regulation Act (RERA) framework had built back some consumer confidence and framed the real estate industry in a different way to what it was before. It was seen as a proactive change in the industry. However, at this point, is the relaxation provided in terms of RERA helpful, or is it a moot point given that things haven’t really started?

PK: The relaxation that is provided under RERA is just a 6-month extension of the delivery timeline the government has provided because of worker unavailability and the loss of time during the lockdown. It hasn’t considered the demand side of the market. I think that the government will have to come forward and extend it further in the future. We have carried out stress testing of over 20,000 housing projects across India and 49% of the supply in the market was in a “high” to a “very high” risk zone regarding construction progress, performance, and demand levels. These projects are susceptible to default even before COVID. Now the problem has aggravated due to the pandemic’s impact on labour, credit flows, and demand. Several housing finance CROs (Chief Risk Officers) that I have spoken with believe that post-COVID, the execution viability of 70% of projects will be under a question mark. This is huge, and the RERA’s 6-month moratorium looks very insufficient. Much more will have to be provided, not only in terms of the extension, but even exemptions of developers from some penal actions they may be liable to.

IHR: What strategic support can the government give to help at this time, not only from the perspective of the consumer and the sector but also from the perspective of labour? A large amount of non-farm work is coming from the construction sector, so what would you think some of the demand-side interventions could be?

PK: Looking at the builders’ supply-side setting, we have around 13,50,000 unsold units valuing close to 9 trillion rupees, and 25% percent of these are in the affordable segment costing less than 50 lakhs. In the past, the government’s demand-side interventions have only been for affordable housing which has motivated developers to shift supply to some extent. However, the majority of the old supply is entangled in units costing more than 50 lakhs and needs demand incentives to free locked-up inventories in the stressed market.

The government should focus on three aspects. One, the interest exemptions limit should be extended from 2 lakh rupees. It is insufficient for individuals buying a property over 1 crore, such as in large cities which have 75% of India’s supply, and doesn’t influence their demand. To motivate customers, the government should provide tax exemptions of up to 12 lakh, which would only impact their revenues by Rs 2200 crore. This amount isn’t much in the broad sense and will be a big motivation for people to purchase property and free locked-up supply.

Second, completed property does not attract goods and services tax (GST). Hence, completed properties were more in demand and the demand for under-construction projects is low. Now, we are in a country where the cost of the capital is over 12% for construction finance. If the builder has to borrow to complete the property he will pass his costs to customers – increasing the selling price and creating a gap between affordability and prices. That’s what has been happening until now, with the extensive financialisation in the market. The government should incentivize sales in the under-construction market, allowing the builders’ cash flow requirements to be met by customer advances and reducing the borrowing for the project. They should waive off GST from under-construction properties, or expand the 1% GST limit for affordable housing for units up to 1 crore rupees. These measures for a year will be a good fillip to real estate.

Third, stamp duties need to be changed. States like Karnataka have already reduced it by 2% and the other states should follow, creating customer confidence and motivation to purchase properties.

IHR: How do you see the post-COVID world looking like for the real estate sector?

PK: I see that COVID has impacted the density aspect of real estate and there will now be a preference towards less dense areas. This would impact job diffusion, where jobs will move to people instead of the opposite which has been the case. Moreover, large cities have started losing out because of their cost of living and the heavier impact of COVID. I feel corporates and people will start looking forward to smaller cities as working from home becomes a possible way of conducting jobs and the new normal.

CPR: Smaller cities may have a barrier in terms of infrastructure levels or lifestyle that is not preferred by a metropolitan crowd. Do you think the new normal is going to lower expectations of people, causing them to live in a decongested and smaller city despite lesser opportunities? Are people going to change the way they think about where they live and where they buy housing?

PK: I think their bigger compulsions are the costs related to living. I feel we didn’t move earlier due to comfort zones and the corporates feeling that they are well settled in certain geographies. My approach to spatial mobility suggests that people aspire to go to the most attractive regions provided they can afford it. But currently, peoples’ salaries and growth prospects are subdued compared to earlier. Several companies are also trying to adopt work-from-home as a permanent aspect. TCS, for example, is making 25% of employees work from home. Thus, diffusion is likely and jobs may move to the peripheries of large cities or to smaller cities. These areas may also gain their own infrastructure which is currently deficient. Overall, the diffusion will mostly be from Tier 3 to Tier 2 cities, and less people will move from Tier 2 to Tier 1 cities due to the latter’s density, costs and poorer work-life balance.

Another side to this I see are emerging concepts such as Make in India which are mostly secondary industry-driven. Manufacturing jobs will grow in smaller places with cheaper land and not surrounding large cities, giving opportunities for jobs in smaller cities to grow.

IHR: When do you see the sector reviving? Is shortage of labour due to migrant exodus an issue?

PK: It is a wait and watch situation for the next few months. Monsoon has now started, which is considered a slightly inauspicious period for purchasing property. Also, labourers may not return if they get jobs back home due to the harvesting season starting from July. This was a yearly occurrence, the monsoon and harvesting period always lead to a lesser number of construction workers available in cities. Further, in places like Mumbai the builders don’t even have the money to bring labourers back and are defaulting on payments to contractors due to insufficient cash flows. Even if they come back, the builders will be unable to pay them. So overall, I think post-Diwali 2020 is when we may see builders bringing down the prices and the government giving some kind of incentive which will fuel a revival.

IHR: That’s right, absolutely, it’s a wait and watch situation. Thank you so much!

(All figures courtesy of Liases Foras. Mr Kapoor had earlier spoken about some of these concerns at an industry webinar on April 30, 2020, and the slides above are from that presentation.)