A major political question for governments around the globe is to determine which form of housing tenure – ownership or rental – would best fit their housing policy agenda. It is now well understood that both forms of tenure need to be taken into consideration as complementary and integral parts of urban housing markets. However, rental housing is not a distinct category, but an umbrella term which covers diverse manifestation of renting a home and various forms of supply. In Latin America, Africa, and Asia, small-scale landlords – who represent a heterogeneous group of housing suppliers – are responsible for much of the rental housing supply. However, they have no political influence and they have stayed invisible to their respective governments, who usually have not supported them. Based on fieldwork conducted in 2019, this piece explores the rental practices in Ambedkar Nagar, a 1990s “sites and services” scheme location in Chennai, India in the context of recent changes in rental legislation in the state of Tamil Nadu where Chennai is located.

The policy context

In India, the policy conversation on rental housing was energised in 2015, when the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (MoHUA), Government of India constituted a Task Force on Rental Housing. The Task Force developed thirteen recommendations which were intended to help the states to improve their urban rental housing markets. These recommendations were also considered in the Draft National Urban Rental Housing Policy 2015 and Draft Model Tenancy Act 2015. The vision of this document, “To create a vibrant, sustainable and inclusive rental housing market in India” (ibid, 2015: 14), clearly shows that the central government started to see the importance of functional rental housing markets in India’s cities. However, while the draft acknowledges the role of small-scale landlords, it stops short of clarifying the role and providing guidelines for their involvment in the housing markets. Its only specific recommendation in this regard is the need for credit facilities and subsidies.

Even though MoHUA did not finalise these policies, based on the Draft Model Tenancy Act 2015, the Government of Tamil Nadu launched The Tamil Nadu Regulation of Rights and Responsibilities of Landlords and Tenants Act (2017) in February 2019. With this act, the state government hopes to encourage private landlords, especially from the middle- and higher-income segments, as well as institutional housing developers to invest in rental housing and to “unlock” properties which were not rented out due to the formerly strong tenant protection regulations.

Rental housing supply in Ambedkar Nagar

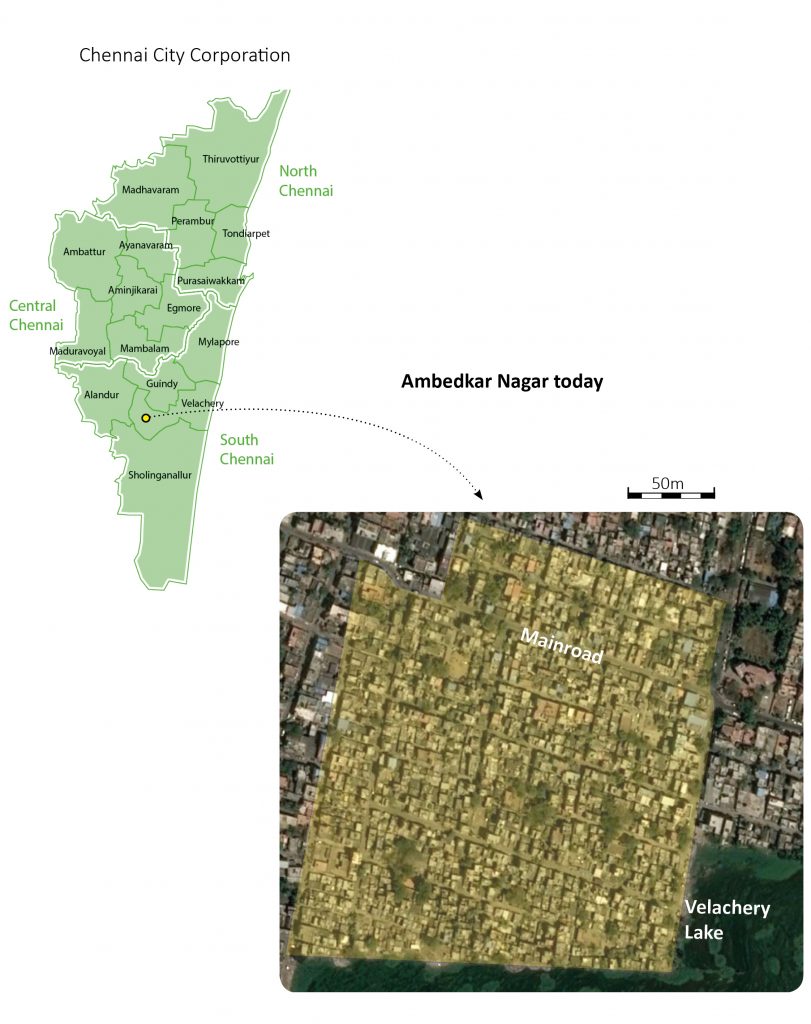

Ambedkar Nagar, a neighbourhood of around 10 hectare, located in the south of the city of Chennai at the Velachery lake, was created at the beginning of the 1990s as a sites and services resettlement. In the last three decades the site has undergone massive transformations, mainly through incremental housing processes. The physical structure and the quality of housing has changed immensely. Many landlords (either initial allottees or buyers) have added floors to their houses, plots have been merged, rooftops have also been constructed over and roads have been paved. Most housing transformations were made in order to expand the floor space to accommodate a growing family or with the intention to rent out rooms.

Multi-story residential buildings in good condition also offer rental spaces for middle-income groups

Due to Chennai’s rapid urbanisation, a once peripheral Ambedkar Nagar is now spatially integrated into the city. It has transformed into a socio-economically and ethnically diverse neighbourhood that accommodates both lower- and middle-income groups. A growing community of internal migrants, including from north-east India has created a robust demand for rental spaces. Numerous small-scale landlords, with various financial means, have created a supply of rental housing in Ambedkar Nagar during the last three decades, offering a wide range of living spaces in terms of quality and price.

The floor spaces are generally small because of the small plot sizes. 1-BHK apartments are the most common form of rental spaces, which can also be found in the multi-story residential buildings. Since living spaces are often occupied by four to five housemates and/or family members, overcrowding is common. Depending on the type of landlord, the apartments are sometimes in good condition with tiled floors and balconies, offering rentals for middle income groups. The cheapest rental spaces are found in the few still existing ‘initial houses’ of the sites and services scheme as well as in the form of ‘simple rooms on terraces’. These typologies have also the worst housing conditions, with basic building materials and poor services.

Initial houses of the sites and services scheme, implemented 30 years ago

| Housing conditions | Water accessibility | Type of landlord | Rent prices (including bills) | Deposits | |

| Initial houses built from the Slum Board | Basic/bad conditions, leaking roofs, includes bathroom | No or restricted access to ground or piped metro water in the house is common, often full dependency on water tankers |

Absentee landlords, subsistence and petty-bourgeois landlords |

2500-4000 INR |

Max. 10.000 INR |

| Simple rooms attached on the terrace | Basic conditions, leaking roofs are common, possibly shared bathroom with neighbours or landlord | No or restricted access to ground or piped water in the rooms is common, access to groundwater well and metro water depends on location and landlord

|

In-situ landlords, subsistence and petty-bourgeois landlords |

2500-4000 INR |

Max. 10.000 INR |

| 1 or 2 Bedroom-Hall-Kitchen (BHK) apartments in a multi-story building, (2 bedrooms are the exception) | Tiled or untiled apartments, often with a balcony and a bathroom are included. | Possible restricted access to water, especially during the dry season. Usually access to ground water and/or metro water | Absentee landlords tend to be petty capitalist landlords, in-situ landlords tend to be petty-bourgeois landlords |

4000-7500 INR |

15.000-30.000 INR |

Table 1: Typologies of rental spaces in Ambedkar Nagar

The metro water pipes have not been maintained in the area with the effect that many households complained that there is either no pressure and therefore no water coming out of the tap, or that only sewage water comes out because the pipes are broken. Water tankers come on a daily basis to the area. Problems with groundwater have become severe in Chennai during the last years because of climate change induced factors such as the rising temperature and the delayed rainy seasons. Pumping up ground water takes up much time (or is temporarily not possible) and leads to a rise in electricity costs, which can sometimes substantially increase the monthly rents and therefore put pressure on both the affordability of the housing costs and the landlord tenant relationships.

Tenancy conditions and secure occupancy

The majority of the rental arrangements in Ambedkar Nagar are based on oral agreements which underlines that the de jure security of tenure for tenants (and in fact for landlords as well) is basically non-existent. The few rentals which had a written agreement were found in properties that had good conditions with an absentee landlord.

The common understanding of landlords in this settlement is that written contracts are only necessary for lease agreements, which includes rather high deposits. Since the lease holders were not aware of the legal steps that are necessary in case their landlords cannot pay back the advance, the legal enforcement of contracts stays vague in the field.

Due to the lack of a legal security in the field, the tenancy conditions and the related de facto and perceptual security of tenure for tenants are therefore formed by trust and complex exchange relationships between landlords and tenants. There are also imposed codes of behaviour that tenants have to follow. For example, not being allowed to have guests or not being allowed to drink alcohol on the premises are among the rules which were mentioned most often. However generally, the landlord-tenant relationships can, with some exceptions, be considered to be quite amicable, personal and harmonic.

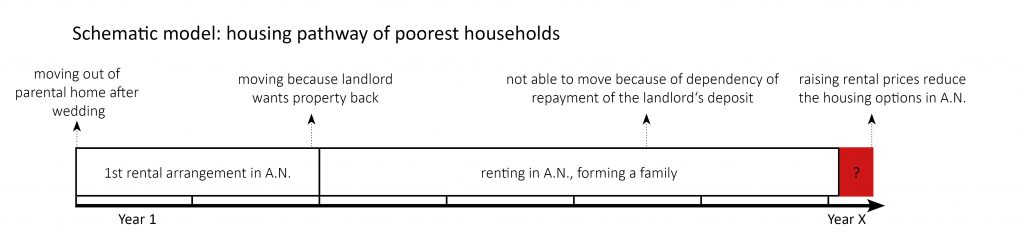

Apart from the relationship towards the landlord, the ability to move and access a new rental space, if and when needed, plays a crucial role in the formation of the de facto and perceived security for tenants. Examining tenants’ patterns of movement have been helpful in identifying the circumstances and constraints that exist within Ambedkar Nagar’s rental market, though these have rarely been explored in the context of low-income rental housing in India. The findings showed that the reasons and numbers of moves of tenants in Ambedkar Nagar varied significantly between households and groups.

For example, local Tamil households who have resided in the area for a long time often relied on social capital, meaning that their social network helped them essentially to find (new) rental spaces. Moreover, being able to speak the local language, which is part of their cultural capital, had considerable advantages for Tamil people to find rental accommodation. In contrast, renters from north-east India mainly found rental spaces through the “to let” board signs which landlords put on their doors. Discrimination based on cultural or religious backgrounds, which would affect the accessibility of the rental market, was not widely reported.

However, the household incomes of north-east migrants tended to be higher compared to large parts of the Tamil population, as they often had work in the formal sector. Because they formed shared households, with multiple earning members, they could also control expenditure better. In this sense, language barriers were offset by their economic capital, which in turn gave the landlords a certain level of trust and the opportunity to maximise their rents. Even though internal migrants from the north-east were unable to rely on their social networks and language skills to find rentals, they generally perceived it as easy to find a living space in the area.

Households which had the financial capacity to regularly adjust their housing situation relocated to improved rental housing because of frequent and long periods of severe water scarcity. Landlords use to ask tenants to pay a deposit which gives them the financial security in case tenants cause damage to the house or do not pay rent. Due to delayed (re-)payments of deposits in the highly informal market, economic capital is crucial to be able to move. A high number of moves, even if they are against someone’s will, indicates a higher control and degree of choice to adjust the housing situation. Very poor households are often trapped in their rental arrangements even though they might want to move to better quality or better located housing.

Besides, cultural differences are reflected in the housing pathways of the local Tamil population and the migrants. Sharing or living in a single-person household is common for migrants who sometimes also form a nuclear family household at a later stage. This stays very much in contrast to the housing pathways and living arrangements of the Tamil population who usually only start renting in the moment they move out of the parental home after getting married. However, some older generations who faced debt problems and therefore needed to sell their plots also started to rent.

Conclusion

The recognition of the importance of tenure neutral policies is crucial in order to meet the housing needs of different groups in the society and provide an effective choice of housing tenures. With the new rental act in place, Tamil Nadu has recognised the relevance of the rental housing sector. The act seeks to rebalance the rights and responsibilities for landlords and tenants, acting on the diagnosis that stronger tenancy rights were inhibiting the supply of rental housing. However, the findings of this research challenge this assumption and find that small-scale landlords, like the ones in Ambedkar Nagar, have produced rental housing for both low- and middle-income groups albeit without formal rental agreements.

New policy measures like Tamil Nadu’s rental act appear to be market driven and have neglected the existing rental housing stock and the various segments of it. Small-scale landlords who accommodate both low-income and middle-income tenants seem to be invisible to the policy makers who appear to be primarily concerned with the expansion and formalisation of the rental markets especially for middle- and higher-income groups.

Planners and policy makers should recognise the existing (informal) markets and their potential. The integral role these markets play in both the urban housing tenure systems and the housing mobility of people cannot be neglected. The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic that triggered a ‘crisis of mobility’ of migrants revealed once more their housing needs, especially for affordable and adequate rental accommodation, which is closely linked to accessing welfare schemes and their social inclusion in urban areas. The development of these market segments, which accommodates most of Chennai’s tenants, including migrant workers, need to be governed and promoted.

New housing policies that have sought to resettle the urban poor on the urban periphery in large-scale housing schemes, like Kannagi Nagar and Perumbakkam in Chennai, have been widely critiqued for further marginalising these communities. Even in Western countries, significant projects like Pruitt–Igoe in St. Louis in the USA or the Bijlmermeer in Amsterdam, built in the second half of the 20th century, are considered failures for reproducing poverty, crime and the stigmatisation of vulnerable groups.

In contrast, research shows that sites and services resettlement areas in Chennai (which encompassed the provision of about 57,000 plots in various locations in the city) have developed to densely populated and economically diverse neighbourhoods which provide a range of housing types in quality and size and offer various forms of tenure. These areas seem to accommodate a substantial number of tenants with different financial means. However, the steadily growing demand of services and lack of maintenance of these neighbourhoods – as seen by perennial problems with access to water in Ambedkar Nagar – call for targeted upgrading schemes. A policy approach that takes into account the local context, would not only recognise and support small-scale landlords in specific laws related to rental housing but also re-emphasize inclusionary land-use policies and incremental housing approaches in order to develop and sustain economically diverse and safe communities in megacities like Chennai.

Very enlightening, as i was reading I had the central city of Johannesburg in SA, also Umtata in the Eastern Cape.