India’s urban landscape is dotted with a diversity of urban areas, where large metros like Delhi or Mumbai co-exist alongside a dense network of small towns. While house-building across the urban spectrum was significant and was equally high in all tiers of cities and towns over the past decade, the leap from houses to housing (viz. access to basic amenities) was not similarly universal over the same period. For example, the share of households living in houses with pucca walls was 98.8% in 2012 in the million-plus cities, compared to 92.3% in smaller towns. Since this number was already high, it only marginally went up to 98.9% in case of million-plus cities and 95.3% in case of other urban areas by 2018, taking up the ratio across them closer to 1. This equally high share of house construction between 2012-2018 (2.1 million pucca houses built in smaller towns and 0.6 million in million-plus cities) was however not similarly reflected in terms of housing infrastructure like exclusive access to piped water, where the ratio was much higher, albeit declining across the same two different size-classes of urban areas, as shown in the chart below.

One of the key differences in terms of houses and housing across various urban size-classes is about ‘who builds’: while building of houses per se in different kinds of urban spaces was facilitated both by private as well as public means (through various Central and State schemes), housing infrastructure seems to be still a privately supplied affair in the smaller towns, whereas the larger cities have varying degrees of public investment in basic infrastructure. In other words, housing in large towns is very much contingent to the development of networked public infrastructure like piped sewerage or piped water supply, while it is dependent upon individual private investments in the on-site facilities like building a septic tank or submersible water pumps on a gradual and incremental basis. This leads to inequities in access to housing, more than houses, within and across various tiers of urban areas in India.

The two graphs above plot the share of households living in houses with pucca walls and the share of households with exclusive access to piped water into the dwelling, across the age of the house (periods since the house is built). While it is evident that both house-building and housing infrastructure is incremental in nature, the gap across large and smaller towns increases over time in case of housing infrastructure, whereas house-building across the spectrum witnesses a convergence.

Thus, public investment in trunk infrastructure has augmented the quality of housing faster in large urban areas, compared to small towns where it is still based upon individual private investment.

This will be clear from the figure above, where Census 2011 data have been used to show the more granular differences across the rural-urban spectrum. The share of households with access to treated tap water, a largely public infrastructure, drops sharply across size-class of towns. On the other hand, the share of improved on-site sanitation, most of which is privately financed, is fairly higher in small towns and unrecognized urban settlements, or Census towns. This signifies that despite high demand, there is minimal public supply of services like piped sewer systems in smaller urban areas.

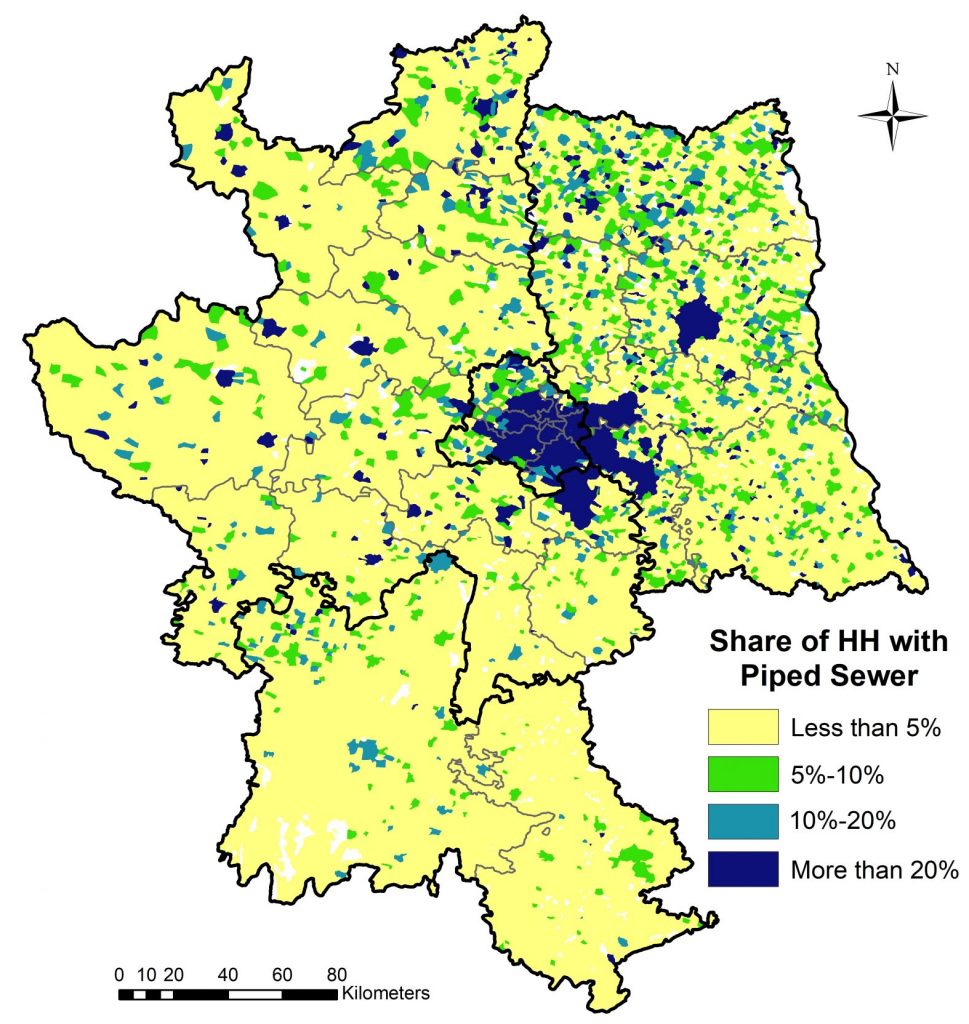

A particularly striking example of this is evident from the map below, where the share of households with piped sewers is plotted across the settlements of the National Capital Region (NCR) to show the geographical concentration of public investment in sanitation, where it is not prevalent even in parts of Delhi and other intermediate towns of NCR. Considering the regional context of planning in NCR, the low prevalence of piped-sewer across its peripheries shows the metro-centricity of public investment in housing in the Indian urban scene.

| Spatial Distribution of Piped Sewer in NCR (2011) |

Small towns play a crucial role in India’s urban scene: a small town consumer spends about 70% of a consumer in million-plus cities (NSSO 68th Round, 2011-12) but receives a far lesser proportion of investment in basic infrastructure. It is important to note here that in recent times, the requirement for networked infrastructure has gone up, given that emergent housing typologies in small towns are very similar to million-plus cities. Therefore, the present state focus in small towns on providing ancillary services for existing private infrastructure (septage management for septic tanks) rather than building networked public infrastructure (sewers) is likely to be environmentally and economically unsustainable in the long term. While the Government’s focus on constructing houses is necessary, a fresh and expanded outlook for better housing infrastructure is also the need of the hour.